As mentioned at the beginning of this blog series, many have suggested that it is time for Hawaiʻi to renegotiate its relationship with the U.S. military, and calls have become louder in recent years. The renegotiation of leases between the Department of Defense and the State of Hawaiʻi provides a rare opportunity to argue for the restoration and return of trust lands – those taken in the illegal overthrow, siphoned away through the territorial period, and leased off for peanuts at statehood.

This renegotiation period also gives us the opportunity to envision demilitarized, more just and regenerative futures and to actively work towards them.

What might Hawaiʻi look like without a military footprint stretching across one-quarter of our archipelago's lands and waters? To even pose the question is to step outside of the tight frame that has long defined Hawaiʻi’s destiny as a “strategic outpost” for the U.S. empire. While visions for the way forward differ, many agree the military hasn’t respected the Hawaiian community, and has a long, historical pattern of destruction and breeding distrust. If we are serious about sovereignty, regeneration, and true security, then we must be willing to imagine—and build—futures where military occupation gives way to a living, thriving lāhui.

The Legalities of Land Return and Restoration

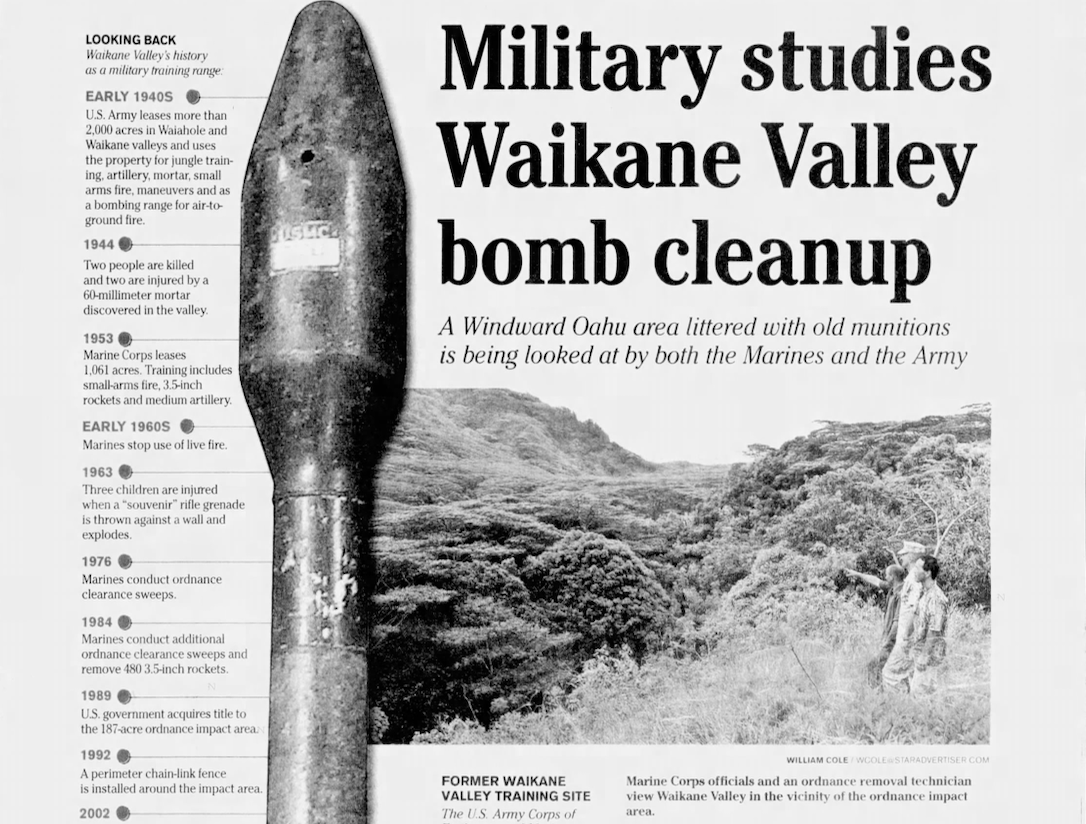

The question of what should happen to Hawaiʻi’s military-occupied lands when leases expire is both political and deeply legal. While international efforts toward rectifying the occupation of Hawaiian lands remain ongoing, even US domestic law recognizes military lands will eventually return to State control. Under Public Law 88-233 (1963), which was an amendment to the 1959 Admission Act, any lands originally part of the Hawaiian Kingdom's public domain and later transferred to the federal government must be returned to the State once they are no longer needed for federal purposes. In theory, these “surplus lands” are not alienated, but held in trust for the people of Hawaiʻi. Yet in practice, for decades, the military has avoided declaring properties surplus, often retaining them through administrative designations or one-sided land exchanges. This has allowed vast tracts of valuable and culturally significant land to remain locked in federal control, with minimal compensation or environmental accountability.

The Hawaiʻi Supreme Court’s decision in Ching v. Case (2019) reinforced that the State, as trustee of the public land trust, has a constitutional duty to ensure that trust lands are properly managed, appraised, and restored when misused or contaminated. The Court made clear that the State cannot passively defer to federal agencies, but that it must actively protect these lands and the public’s interest in them. The case reinforces both the legal authority and moral obligation for Hawaiʻi to demand fair valuation, environmental remediation, and eventual reversion of military lands to public and Native Hawaiian stewardship.

Together, these legal precedents remind us that land return is not an act of generosity, but a matter of justice and law. As we face the expiration of key military leases, instead of defaulting to another generation of $1/year leases, Hawaiʻi could choose to reimagine these lands as sites of restoration, renewable energy, and cultural resurgence, honoring both the legal mandates of return and the moral imperative to heal what militarization has damaged.

Reimagining Military Land

If demilitarization were realized, the question becomes: What becomes of the lands and who gets to decide?

- Housing for Kamaʻāina: Approximately 48,500 active-duty service members and reservists are stationed in Hawaiʻi and service members occupy about 13.86% of private, occupied rental units on Oʻahu. Imagine the military’s residential neighborhoods in Kāneʻohe, Wahiawā, and Pearl Harbor converted into affordable housing cooperatives for kamaʻāina families, rather than enclaves for transient service members. In addition to housing, military bases could be closed and converted to other productive uses, such as facilities for education, research, technological innovation, social services, and other community organizations. Building on the experiences of Kahoʻolawe and other military land restoration projects, Hawaiʻi firms and workers can become leaders in the growing field of environmental restoration of former military sites. The vast, water-intensive golf courses at places like Barber’s Point and Hālawa could be transformed into regenerative agroforestry systems, reviving ancestral economies of abundance.

- Hale Koa Reborn: The beachfront hotel reserved for U.S. service members and their families could be repurposed as a cultural center and regenerative tourism hub, where visitors support local artists, farmers, and practitioners rather than military subsidies.

- Beaches Back: Though there is no definitive, comprehensive list of all beaches currently leased by the U.S. military in Hawaiʻi, a few known beachfront properties that might revert if leases were not renewed include (in addition to Hale Koa in Waikīkī): Mokulē‘ia Army Beach on Oʻahu (near Waialua); Barbers Point (White Plains / Nimitz Beach) cottages operated by the Navy as beachfront recreation cottages; PMRF Barking Sands on Kauaʻi; Mōkapu Peninsula is currently inhabited by Marine Corps Base Hawaiʻi, which is approximately 2,951 acres and includes several coastal shorelines (“North Beach” is a popular surf spot); and Pōkaʻi Bay, currently home to the Pililāʻau Army Recreation Center, which includes beachfront cabins.

These lands, once touted as “improved” through military engineering, could instead be restored as centers of food security, education, and regeneration.

From National Security to Genuine Security and a Regenerative Economy

The U.S. government has long justified its vast holdings in Hawaiʻi in the name of “national security.” Bases like Marine Corps Base Hawaiʻi in Kāneʻohe (Mōkapu) were seized or consolidated with claims that the military could “improve” the land, providing jobs and infrastructure. But this framing ignores what security truly means. National security protects empire; genuine security protects ʻāina and people, ensures that kamaʻāina have homes, and that cultural practices can thrive. It is not secured by fleets and fighter jets, but by healthy ecosystems, equitable housing, and resilient local economies.

The GDP-centered model, which counts military contracts and base operations as “economic drivers,” masks the true costs of contamination, displacement, and dependency. A regenerative economy would measure health differently: in acres of loʻi restored, families housed, renewable energy produced, and cultural knowledge sustained. Already, we see seeds of this future. Community-led fishpond revitalization projects are bringing back ancestral food systems. Energy cooperatives are moving toward renewables rooted in local control. Kalo and ʻulu farmers are reconnecting land, food, and cultural practice.

A demilitarized Hawaiʻi could scale these efforts, redirecting billions in military spending toward infrastructure that sustains life rather than destroys it.

Lessons from the World

Hawaiʻi would not be the first place to emerge from military and colonial control into sovereignty and prosperity. Singapore, once a British naval stronghold, reinvented itself after independence as a hub for finance, trade, and education. When Singapore became fully independent in 1965 after separating from Malaysia, its GDP per capita was roughly US $516. Between 1960 and 1990, Singapore’s per capita GDP rose almost 30-fold. In the decades after independence, Singapore successfully shifted from low-skill and labor-intensive industries to higher-value manufacturing and services (finance, logistics, etc.), strong public housing programs, and heavy investment in education and infrastructure.

Other nations in the Pacific and Caribbean have also shifted away from externally imposed bases to chart their own development paths. One such example is Mauritius, a strategic base for colonial navies (first French, then British) in the Indian Ocean until 1968. Though not as heavily militarized as Hawaiʻi, it was treated primarily as a military/naval outpost and plantation colony. At independence, Mauritius was considered vulnerable: small, isolated, with a monocrop (sugar), and little in the way of industry, with many economists at the time predicting failure. Instead, Mauritius deliberately pursued diversification strategies: modernizing its agricultural sector, then diversifying into tea, seafood, and high-value crops; attracting investment in textiles and light industry; growing into a regional hub for offshore finance and information technology, and more recently, investing in renewable energy and sustainable development. Poverty declined sharply, literacy and education levels rose, and Mauritius has been called the “African success story” because it transitioned from dependency and colonial control to a diversified, resilient economy.

Each example is imperfect, but together they remind us that dependency is not the only option.

Toward Aloha ʻĀina Futures

Demilitarization is not just about the removal of bases; it is about accountability and true restoration. It is about repairing contaminated lands, returning illegally occupied spaces to Native stewardship, and uplifting the ancestral systems that once sustained these islands for generations. It is about imagining—and building—futures rooted in aloha ʻāina.

Toward a demilitarized Hawaiʻi is toward a liberated Hawaiʻi.

SOURCES:

“To Cede or to Seed: Has the election changed the State of Hawaiʻi’s approach to the expiring military leases?,” Ka Wai Ola (Dec. 1, 2024).

Kyle Kajihiro & Ty Tengan, “The Future is Koa,” in The Value of Hawaii 3: Hulihia (2020).

Kevin Knodell, “Service members occupy nearly 14% of Oahu rentals, Pentagon says,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser (Jan. 20, 2025), https://www.hawaiitribune-herald.com/2025/01/20/hawaii-news/service-members-occupy-nearly-14-of-oahu-rentals-pentagon-says.

Jim Zarroli, “How Singapore Became One Of The Richest Places On Earth,” National Public Radio (March 29, 2015), https://www.npr.org/2015/03/29/395811510/how-singapore-became-one-of-the-richest-places-on-earth.

The World Bank in Mauritius, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/mauritius/overview

Arvind Subramanian, “Mauritius: A Case Study,” International Monetary Fund Finance & Development vol. 28, issue 4 (Dec. 2001), https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2001/12/subraman.htm