There is no doubt that one of the driving reasons for the U.S. attempts to Annex Hawaiʻi was to shore up U.S. military influence in the Pacific. By the late 1860s, U.S. diplomats stationed in Hawaiʻi began to view the islands as a vital outpost for the defense of trade routes to Asia. American sugar planters seized on this renewed interest by tying it to debates over sugar tariffs, blending commercial and military objectives in ways that would eventually lead to the illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government.

U.S. Military Presence Leading up to the Overthrow

- American troops had been present in Hawaiʻi since the 19th century, and by the late 1800s, their role shifted from “protection of American lives and property” to active enforcement of regime change. The presence of these troops was not incidental. It was foundational to the loss of Hawaiian governance and the establishment of Hawaiʻi as a U.S. military outpost.

- The U.S. Navy established a regular presence in Hawaiʻi when it began leasing land in Honolulu in 1860 for a coaling station.

- In 1887, under pressure from the Honolulu Rifles - a militia composed largely of American and European residents with U.S. support - King Kalākaua was forced to sign the so-called Bayonet Constitution. It stripped the monarchy of much of its authority, disenfranchised Native Hawaiian voters, and handed political power to foreign residents and sugar interests. This weakening of Hawaiian governance directly enabled the illegal overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893, carried out with the backing of U.S. Marines.

- U.S. marines and the military influence of the USS Boston in Honolulu Harbor supported American insurrectionists in their illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom government on January 17, 1983. When Royalists loyal to Queen Liliʻuokalani attempted to regain control of the government in 1895, the USS Philadelphia, an American warship, helped quell the uprising.

1900–1940s: Building the “Fortress” of the Pacific

“Oahu is to be encircled with a ring of steel, with mortar batteries at Diamond Head, big guns at Waikiki and Pearl Harbor, and a series of redoubts from Koko Head around the island to Waianae.”

General Macomb, U.S. Army Commander, District of Hawaii 1911 (quoted in Addleman, 1946: 9)

- By the early 20th century, Hawaiʻi was dotted with forts, airfields, and training areas. Construction of a naval base at Pearl Harbor began in 1900, destroying 36 traditional Hawaiian fishponds and transforming what had been a rich food source into a naval stronghold. This was followed by the construction of Fort Shafter, Fort Ruger, Fort Armstrong, Fort DeRussy, Fort Kamehameha, Fort Weaver, and Schofield Barracks.

- By 1900, the U.S. military had taken control of 16,500 acres; by 1920, it controlled 22,000 acres. During this period, the local business community exerted immense political pressure in support of an increased military presence in Hawaiʻi. In fact, in 1905, both the Chamber of Commerce and the Merchants Association of Honolulu urged Congress to provide additional funds for military development.

- Americans stationed here from the 1800s to 1950s: According to the United States Census of the population in the Hawaiian Islands from 1900 to 1950, migration from the continental U.S. and its territories in fifty years totaled 293,379.

- In the 1920s–1930s, military expansion accelerated through executive orders and land swaps under the Territorial government. These seizures often targeted Hawaiian homelands and coastal communities, displacing families and severing connections to ʻāina. At Mākua Valley on Oʻahu’s Waiʻanae Coast, Native Hawaiian families were evicted under the promise that they could return after World War II. Instead, the valley was bombed and occupied for decades.

- The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 only deepened militarization. Hawaiʻi was placed under martial law for nearly three years—civil rights suspended, newspapers censored, curfews enforced, and residents (especially Japanese Americans and Native Hawaiians) subjected to surveillance and suspicion.

1950s–1970s: Statehood, Expansion, and Political Controversy

- After World War II, the onset of the Cold War fueled even more expansion. Hawaiʻi became a key staging ground for Pacific operations, including nuclear weapons testing across Micronesia.

- When Hawaiʻi was claimed as a state in 1959, it entered into a series of Public Land Trust (PLT) leases with the federal government. In many cases, the state was effectively compelled to lease large tracts of land—often at nominal rates—to the U.S. military. This locked Hawaiʻi into a pattern where lands taken during the overthrow and Territorial period were not restored to Native Hawaiians, but instead ceded to military control. Key sites included:

- Kahoʻolawe: Used as a live-fire training target from 1941 to 1990, sustaining decades of bombing that scarred the island and desecrated sacred sites.

- Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA): Expanded into the largest U.S. training ground in the Pacific, covering 133,000 acres of culturally and ecologically sensitive land.

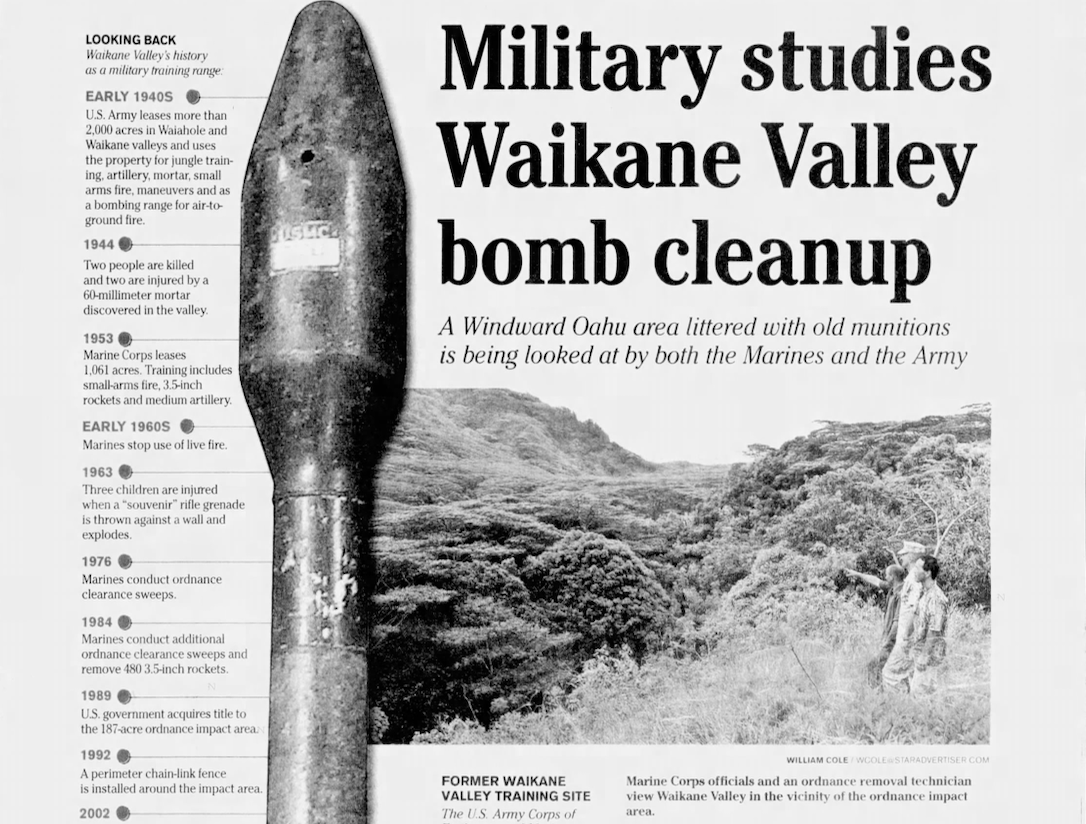

- During this era, Hawaiʻi also witnessed community resistance. In January 1976, nine activists made the first successful landing on Kahoʻolawe to protest its use by the U.S. military as a bombing range. This action led to the establishment of the Protect Kahoʻolawe ʻOhana (PKO) and the renewed aloha ʻāina movement, which inspired legal and political battles to protect natural and cultural resources across the paeʻāina. In the 1970s, residents of Waikāne Valley on Oʻahu fought the Navy after live-fire training contaminated their land and water. The prolonged struggle highlighted how military activity endangered not only sacred lands but also public health.

1980s–1990s: Resistance and the Start of Cleanup

- Decades of protests, occupations, and lawsuits ultimately forced the military to halt bombing Kahoʻolawe in 1990 and begin cleanup. Yet only about 75% of the surface and less than 10% of the subsurface of Kahoʻolawe have been cleared of unexploded ordnance. The island remains hazardous and largely inaccessible.

2000s–Present: Ongoing Environmental Impacts and Political Struggles

- Today, Hawaiʻi hosts the headquarters of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, with over 73,000 active-duty and civilian personnel and nearly $10 billion annually in defense spending.

- The military controls approximately 222,000 acres statewide, including about 25% of Oʻahu.

- In 2021, the catastrophic fuel leak from the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility poisoned Oʻahu’s drinking water, sickening thousands and highlighting the risks of storing massive fuel reserves above a sole-source aquifer, which environmental and Native Hawaiian advocates have warned about for years.

- In 2025, the Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resources rejected Army lease renewals for training lands at Pōhakuloa and Oʻahu sites, citing inadequate environmental and cultural review.

The Real Economic Consequences of Continued Military Occupation

- The real economic costs of continued military occupation are staggering, though rarely calculated in official reports. Across the islands, lands of immense cultural, ecological, and monetary value have been seized through eminent domain or locked into long-term federal leases, often for as little as $1 for 65 years, effectively stripping Hawaiʻi of billions in potential revenue. Places like Mākua Valley, where Hawaiian families were evicted in the 1940s under “temporary” military orders, remain largely off-limits and contaminated, despite court rulings that the Army failed to complete adequate environmental review. During the 1970s, Waikāne residents were forced into a legal settlement after resisting condemnations that transferred fertile taro lands into military hands, with compensation at way below market value. The Pōhakuloa Training Area, the largest live-fire training ground in the Pacific, is leased under terms so lopsided that Hawaiʻi receives virtually no return, even as nearby ranch lands sell for tens of thousands of dollars per acre.

- In 2012, nearly the entire island of Lānaʻi was purchased by businessman Larry Ellison approximately $300 million, or about $3,336 per acre, illustrating the scale of value associated with large tracts of Hawaiʻi land. By contrast, Kahoʻolawe’s 28,776 acres, though severely damaged by decades of military bombing and now held in trust for restoration, could be conservatively valued between $144 million and $863 million if assessed at standard agricultural or conservation rates. While the U.S. military no longer leases Kahoʻolawe, the comparison highlights the immense opportunity costs Hawaiʻi has absorbed: lands rendered economically unproductive and uninhabitable by militarization, and the long-term burden of restoration shifted to the state rather than compensated through lease revenues or damages.

- Appraisals of military leased land are nonexistent in public records, but independent estimates suggest that if even a fraction of these lands were restored to agriculture, or leased for conservation and renewable energy at market rates, or even developed, Hawaiʻi could generate revenues in the billions annually. For instance, if the U.S. military leases 6,000+ acres of state land on Oʻahu (e.g. Kahuku, Poamoho, Mākua) for $1, and the real market value is, conservatively, $30,000/acre (agricultural or rural value), that’s about $180 million/year in foregone revenue by the state, just from those acres alone.

- Lands that are made unusable by live-fire training, bombing, or contamination may have their economic value severely depressed—even close to zero—while still being locked into military control. This means not only lost revenue, but lost use (agriculture, cultural use, housing, conservation).

- Even the state, which has historically caved to federal powers on these issues, has acknowledged the scale of potential economic loss and the need to push for baseline data (appraisals) to ensure any future leases are not grossly unfair. In April 2024, the BLNR discussed the issue but ultimately deferred decision-making on getting appraisals on the lands leased to the military. At a minimum, the absence of comprehensive land appraisals underscores a broader issue: the true cost of militarization is systematically hidden, leaving residents to bear both the economic loss and the environmental damage.

Impacts on Social and Community Well-Being

- The social costs of militarization extend far beyond the bases’ fences, shaping everyday life for Hawaiʻi’s communities in ways that are often hidden. In Waikāne Valley, residents have repeatedly uncovered unexploded ordnance from decades of live-fire training, forcing families to abandon ancestral ʻāina that once sustained them physically and spiritually. At Mākua, evictions and weapons testing left behind contamination and lingering fears for those who still live nearby. Even in residential areas adjacent to Schofield Barracks and other Oʻahu training sites, families have reported finding artillery shells or munitions on their properties – stark reminders that military activity does not stay confined to its training grounds.

- These dangers are compounded by long-term contamination of soil and water, creating uncertainty for generations who live nearby. At the same time, the massive military presence has influenced Hawaiʻi’s cultural identity, pushing assimilation into American patriotism and military culture at the expense of Hawaiian language and traditions. The result is a social landscape where many accept danger and displacement as the price of “security,” even as the true costs are borne disproportionately by Hawaiian communities living closest to military lands. For instance, in areas like Waimea on Hawaiʻi Island, where school curricula and safety drills include instruction on unexploded ordnance and military explosives, children bear a hidden social cost, normalizing exposure to danger as part of daily life.

Why This History Matters

The story of the U.S. military in Hawaiʻi is not just about geopolitics—it’s about land, water, and self-determination. It is about how Native Hawaiians were dispossessed of governance and access to sacred places. It is about how fragile ecosystems were damaged and destroyed by bombing, contamination, and overuse over decades. It is about how militarization reshaped housing, the cost of living, and daily life for everyone who calls Hawaiʻi home. It is about the many political leaders that have failed to speak against the impacts of the military industrial complex in our islands, and the courageous few who spoke the truth to power.

Understanding this history is essential if we are to imagine a different future: one where Hawaiʻi is not just a “strategic outpost,” but a living homeland where ʻāina, kānaka, and community can thrive.

SOURCES:

Kathy E. Ferguson and Phyllis Turnbull, Oh, Say, Can You See?: The Semiotics of the Military in Hawaiʻi (1998).

Kyle Kajihiro and Terri Lee Kekoʻolani, “The Hawaiʻi DeTour Project: Demilitarizing Sites and Sights on Oʻahu,” in Detours: A Decolonial Guide to Hawaiʻi 254 (Hōkūlani Aikau & Vernadette V. Gonzalez eds., 2019).

Kyle Kajihiro, “The Military Presence in Hawaiʻi, Island Breath (blog) (March 1, 2007), http://www.islandbreath.org/2007Year/17-peace&war/0717-17HawaiiMilitarism.html.

I.Y. Lind, “Ring of Steel: Notes on the Militarization of Hawaii,” Social Process in Hawaii 31, (1984-85), 25.

Jon Osorio, Dismembering Lāhui: A History of the Hawaiian Nation to 1887 (2002).

David Keanu Sai, “American Occupation of the Hawaiian State: A Century Unchecked,” Hawaiian Journal of Law & Politics (2004), 63 (citing “Table 18. Country of Birth, for Hawai’i, Urban and Rural, 1950, and for Hawai’i, 1900 to 1940,” U.S. Census of Population: 1950, Department of Commerce, 52-18).

Noenoe K. Silva, Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism (2004).

Sophie Alexander, “Larry Ellison’s Lanai Isn’t for You – or the People Who Live There,” Bloomberg (June 8, 2022), https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2022-oracle-larry-ellison-lanai-hawaii-plans-tourism.

Thomas Heaton, “The Days Of The Army Leasing Land In Hawaii For $1 Are Likely Over. But What’s Next?,” Honolulu Civil Beat (Apri 28, 2024), https://www.civilbeat.org/2024/04/the-days-of-the-army-leasing-land-in-hawaii-for-1-are-likely-over-but-whats-next/.

Thomas Heaton, “State Rejects Army Analysis of Its Impact on Oʻahu Training Sites,” Honolulu Civil Beat (June 27, 2025), https://www.civilbeat.org/2025/06/state-rejects-army-analysis-of-its-impact-on-o%CA%BBahu-training-sites.

Kuʻuwehi Hiraishi, “Land board defers decision on appraisal of lands leased by US Army,” Hawaiʻi Public Radio (April 16, 2024), https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/local-news/2024-04-16/land-board-defers-decision-on-appraisal-of-lands-leased-by-us-army.

Christina Jedra, “Is It Time For Hawaii To Renegotiate Its Relationship With The Military?,” Honolulu Civil Beat (May 2022), https://www.civilbeat.org/2022/05/is-it-time-for-hawaii-to-renegotiate-its-relationship-with-the-military/.

Army Training Land Retention on Oahu, Environmental Impact Statement – Home, U.S. Army, https://home.army.mil/hawaii/OahuEIS/project-home

Army Training Land Retention at Pōhakuloa Training Area: Environmental Impact Statement – Project Home, U.S. Army, https://home.army.mil/hawaii/ptaeis/project-home

Hawaii Military Land Use Master Plan, 2021 Interim Update, US Indo-Pacific Command (April 2021).

Development of the Naval Establishment in Hawaii: The U.S. Navy in Hawaii, 1826-1945: An Administrative History, Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/u/the-us-navy-and-hawaii-a-historical-summary/development-of-the-naval-establishment-in-hawaii.html.