Hawaiʻi stands at a pivotal moment. For more than a century, the islands have carried the weight of the U.S. military’s presence—shaping our history, economy, and daily life in ways both visible and unseen. That legacy continues today, as critical questions over land, water, and sovereignty take center stage.

In recent months, the BLNR has rejected both of the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statements (FEISs) to retain training lands at Pōhakuloa and on Oʻahu (Kahuku, Poamoho, and Mākua), citing missing environmental, cultural, and safety data, amongst other issues. As a result, the military has pushed to accelerate its timelines for renewing these long-term land leases and advancing training projects, citing urgency for national security reasons. U.S. Army Secretary Dan Driscoll said he wants a “mutually acceptable framework” finalized by the end of the year, which would compress careful environmental review, public consultation, and cultural assessment into a potentially rushed timeline. Hawaiʻi’s governor has responded cautiously, proclaiming the strategic importance of the military while also stressing that community trust and environmental safety cannot be compromised. He has also suggested the federal government could legally invoke eminent domain to take land if agreements aren’t reached.

Many fear this will all unfold without open, inclusive, or transparent stakeholder engagement, leading to outcomes that ignore environmental and cultural safeguards. On September 2, 37 Native Hawaiian organizations stood together at ʻIolani Palace to deliver a historic joint statement on the expiration of U.S. military land leases in Hawaiʻi and to encourage other organizations to join in a unified call for Governor Green and the State of Hawaiʻi to:

1) Provide Native Hawaiian community representation in all lease negotiations;

2) Pursue cleanup and the return of lands to Native Hawaiian stewardship;

3) Ensure accountability, restitution, and compliance with state and federal law; and

4) Uphold transparency and the principle of free, prior, and informed consent.

Time and time again in several struggles over land and military control, the U.S. military has repeatedly framed its occupation of Hawaiʻi as unescapable, arguing that any reduction in its land holdings would disrupt critical operations and spell economic disaster for Hawaiʻi, and that completing clean-up efforts would force an undue burden on taxpayers. From Kahoʻolawe and Mākua Valley to Pōhakuloa and Kapūkakī, Native Hawaiian communities have spoken out against both the state and the federal government’s mismanagement and degradation of lands, highlighting the need to contextualize the ongoing social, cultural, and environmental impacts of continued U.S. military presence in Hawaiʻi.

This tension—between promises of security and the lived reality of occupation—underscores the importance of revisiting the past, understanding the present, and imagining a more just future for Hawaiʻi’s economy, people, and place. In this blog series, we’ll explore these themes: the history of militarization, its current impacts, and what a demilitarized future might look like.

Present: The Hidden Costs of Continued Military Occupation in Hawaiʻi Today

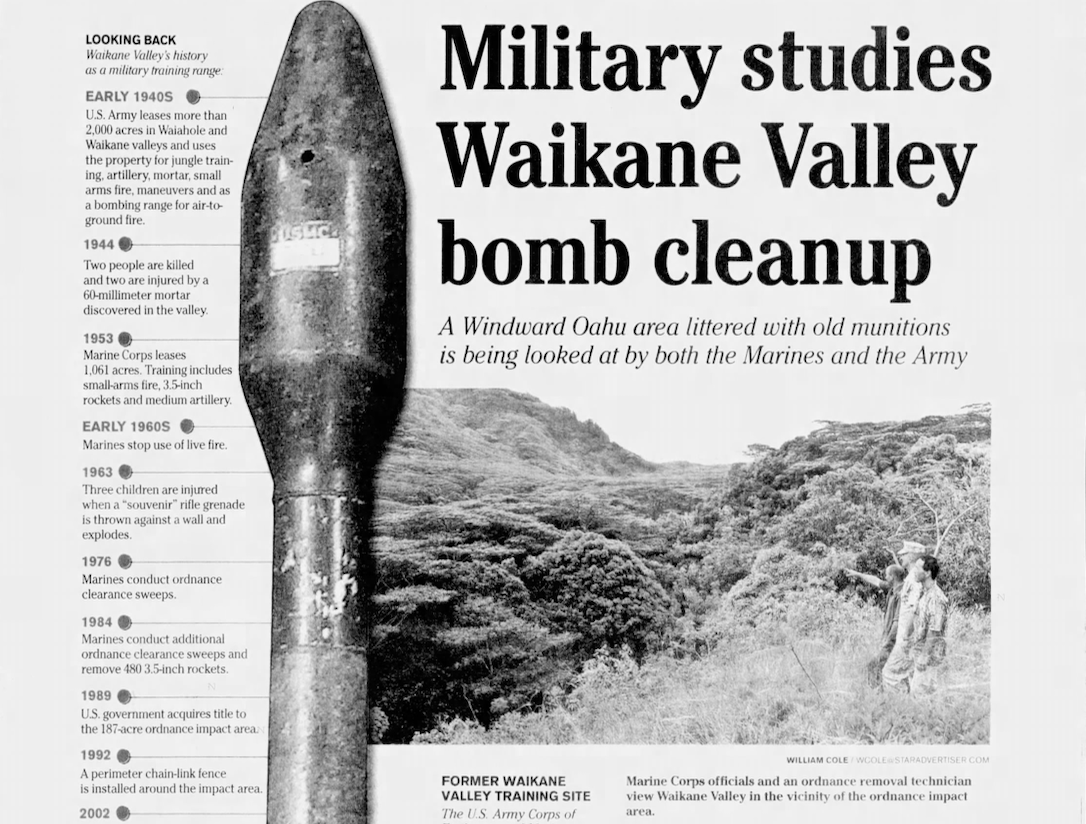

The magnitude of the United States’ (U.S.) military presence in Hawaiʻi today is staggering. Kanaka Maoli scholar-activist Kaleikoa Kaeo described the military in Hawaiʻi as a monstrous he‘e (octopus), “its head represented by the Pacific Command headquarters, its eyes and ears the mountaintop telescopes, radar facilities, and underwater sensors, and its brain and nervous system the supercomputers and fiber optic networks that crisscross the islands.” This heʻe excretes waste as toxic land, polluted waters, and depleted uranium. As scholars Kyle Kajihiro and Ty Kawika Tengan have observed, the U.S. military has bombed and desecrated hundreds of sites, including Kahoʻolawe, Mākua, Pōhakuloa, Līhuʻe, and Waikāne, “transforming these wahi pana (storied places) into forbidden zones contaminated with unexploded munitions and toxic chemicals” and by doing so, the military “holds the future hostage—severing indigenous relations to land and foreclosing on alternative uses.”

Indeed, the military currently controls more than 230,000 acres across Hawaiʻi, which house 118 military sites, and commands 24.6 percent of Oʻahu’s lands alone. In addition to its federal holdings, the military currently leases approximately 30,000 acres from the state under 65-year leases for one dollar for the length of each lease. These leases will expire in 2029, raising many questions about what the U.S. military is willing to do to hold on to these lands, what the state can and should do in pursuit of legal and moral justice, and what the greater community, and Kānaka Maoli in particular, can do in calling for the return and restoration of these lands.

The U.S. military’s substantial presence has not only shaped Hawaiʻi’s geopolitical importance but also deeply affected the daily lives of its residents—particularly in terms of housing, the cost of living, and the displacement of Native Hawaiians.

The Military’s Dominance

Various reports have touted the U.S. military as the second largest sector of Hawaiʻi’s economy after tourism. As of 2021, the DoD directly employs approximately 55,000 personnel in Hawaiʻi, and the overall defense sector, including contractors and support staff, contributes around $13.8 billion annually to the state’s economy. While this may sound like a boon, the hidden costs of this military occupation are felt most acutely by the local population, particularly Native Hawaiians and working-class residents.

Housing Crisis and Military Expansion

One of the most significant impacts of the U.S. military presence in Hawaiʻi is its contribution to our collective housing crisis. The federal government’s large landholdings, spanning more than 230,000 acres (about 10% of Hawaiʻi’s total land area), have artificially constrained the housing supply. This has driven up property values and rent prices, making it increasingly difficult for local residents, especially Native Hawaiians, to afford stable housing.

According to the Pentagon, there are roughly 48,500 active-duty service members and reservists stationed in Hawaiʻi, with service members occupying nearly 14% of Oʻahu rentals. While many of Hawaiʻi’s political and business leaders have touted their presence and spending as a boost to the local economy, their influence on the housing market has at times been a subject of fierce debate. Military housing allowances in some cases give service members and their families an advantage in looking for housing, which some have charged contribute to high rents as local families struggle with rising costs of living. For instance the “Basic allowance for Housing” (BAH) is a stipend given to service members to use toward securing a rental property, and Joint Base Pearl Harbor has some of the highest rates granting soldiers and officers with dependants between $3,204 - $4,827 a month just to use toward housing. While those on Maui and Kauaʻi are granted even higher ranges that end near $6,800 a month for some Maui service members. How can locals compete for rental housing when they do not have access to the same kinds of rent subsidies programs? In fact, many of us couldn't and this had contributed toward the displacement of many local families.

Displacement of Native Hawaiians

Native Hawaiians—who already face deep historical and socioeconomic challenges—have been particularly affected by the housing crisis. The illegal overthrow and forced annexation of Hawaiʻi by the United States and its subsequent militarization led to the displacement of thousands of Native Hawaiians from their ancestral lands. Today, Native Hawaiians make up only about 20% of the state’s population but are disproportionately impacted by housing insecurity.

A study by the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation in 2020 found that nearly 30% of Native Hawaiians live below the federal poverty line—significantly higher than the state average. The military’s occupation of valuable land has contributed to this poverty by preventing the development of housing that could support the growing population, particularly for lower-income Native Hawaiian families.

As the housing market becomes increasingly unaffordable, many Native Hawaiians are being forced to relocate to the neighboring islands or the U.S. mainland in search of affordable housing. This exodus is exacerbated by the loss of traditional lands and cultural spaces, as military training and testing operations continue to encroach on sacred Native Hawaiian sites. The forced relocation of families represents a continuation of the colonial legacy of the U.S. occupation in Hawaiʻi.

Inflation of Goods and Services

Beyond housing, the military’s dominance in Hawaiʻi also affects the general cost of living, making it more difficult for local residents to make ends meet. The increased demand for goods and services, especially in communities near military bases, inflates prices for food, healthcare, utilities, and other essentials. While military personnel benefit from subsidies such as tax exemptions and on-base shopping at discounted rates, local residents do not have access to these advantages.

The state also has some of the highest energy costs in the nation. The U.S. military is the largest consumer of energy in Hawaiʻi, and its need for power often creates fluctuations in supply and demand that impact civilian prices. Many residents face electricity bills that exceed $300 per month, adding another strain to their already stretched budgets.

Environmental Degradation

The U.S. military’s misuse of Hawaiʻi’s land and natural resources has also led to environmental degradation. Live-fire exercises, bombing runs, and the testing of military equipment have left lasting scars on the landscape, damaging water sources, marine life, and ecosystems that local communities rely on. Native Hawaiians are particularly vulnerable to the destruction of sacred sites and traditional food sources.

For example, in 2021 the Red Hill fuel tank leak near Pearl Harbor caused significant contamination of the local water supply, affecting the health of thousands of residents. The military’s negligence in maintaining its facilities led to a crisis that exposed the vulnerabilities of local communities to the consequences of military operations. Community groups like Kaʻohewai, Oʻahu Water Protectors, and the Sierra Club mobilized to call for shutting down of the Red Hill tanks, which were eventually decommissioned and mostly drained of fuel, though sludge and residue remain.

The measure of prosperity in Hawaiʻi cannot be a single GDP growth percentage. Billions of dollars are counted toward Hawaiʻi’s GDP through militarism, however, if those dollars simply destroy our island’s precious ecosystems leaving behind unusable landscapes littered with unexploded ordinances or aquifers poisoned with jet fuel–can anyone honestly say that this is the kind of economy Hawaiʻi deserves? Our islands deserve better and leaders should recognize, there is no alternative to a livable environment and safe and clean drinking water. A more accurate measure of prosperity must be tied to community and environmental health. It is not just about measuring financial metrics, it must also include indicators on whether our waters are clean, our lands are healthy, and Kānaka ʻŌiwi can thrive in our homelands. Recognizing the true, hidden costs of militarization is the first step toward policies that put Hawaiʻi’s people and places first.

Call to Action: Submit Comments

Governor Green launched a website for community input on the accelerated timeline proposed by the Army for renewing land leases and proceeding with training projects. It is crucial to make our voices heard and advocate for careful environmental review, community consultation, and extensive cultural assessment in this process.

Visit this webpage by the Sierra Club of Hawaii for instructions and sample comments.

Sources:

N. Mahina Tuteur, Davianna McGregor, Kaulu Luʻuwai, Forthcoming chapter on Militarization in Native Hawaiian Law: A Treatise (2d ed.).

Kristen Consillio, Native Hawaiians fight for sacred lands as military leases near expiration, KITV (Sept. 2, 2025).

Kyle Kajihiro & Ty Tengan, The Future is Koa, in The Value of Hawaii 3: Hulihia, The Turning (2020).

Board of Water Supply. 2025. Red Hill Information. Honolulu Board of Water Supply.

Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism (DBEDT). 2024. State of Hawaiʻi Data Book. https://dbedt.hawaii.gov/economic/databook/.

Department of Defense, Office of Local Defense Community Cooperation (OLDCC). 2023. Defense Spending by State, FY2023.

Department of Defense, Report to Congress: Joint Housing Requirements and Market Analysis for Certain Military Installations in Hawaii (2025), available at https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/i64arf99l345v4ioue89y/05-TAB-B-FY-2024-NDAA-Section-2874-HI-HRMA-80.pdf?rlkey=2km57837c2rcawxhhsgm9op37&e=1&st=c4i73p1u&dl=0.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2025. Red Hill Underground Storage Tank Facility. https://www.epa.gov/red-hill

Hawaiʻi Housing Finance and Development Corporation (HHFDC). 2024. Hawaiʻi Housing Planning Study 2024. Prepared by SMS Research.

U.S. Army Garrison Hawaiʻi. 2025. Pōhakuloa Training Area. https://home.army.mil/hawaii/ptaeis/project-home.